In a dimly lit cinema on a January evening, an unusual sight unfolds: rows filled with twenty-somethings eagerly awaiting a 50-year-old surrealist film about religious enlightenment and existential transformation. Not the latest A24 offering, not a Marvel release, but Alejandro Jodorowsky's 1973 cult classic "The Holy Mountain."

This scene, described by screenwriter Anthony Mullins in his essay "Young Pilgrims on Cinema’s Holy Mountain" for Australian arts publication FilmInk last summer, isn't anomalous. It represents a growing phenomenon across cinemas from Brisbane to Bristol, London to Los Angeles. The repertory film sector—screenings of classics, cult favourites, and arthouse treasures from decades past—is experiencing a surprising renaissance, driven largely by the demographic least expected to champion it: Generation Z.

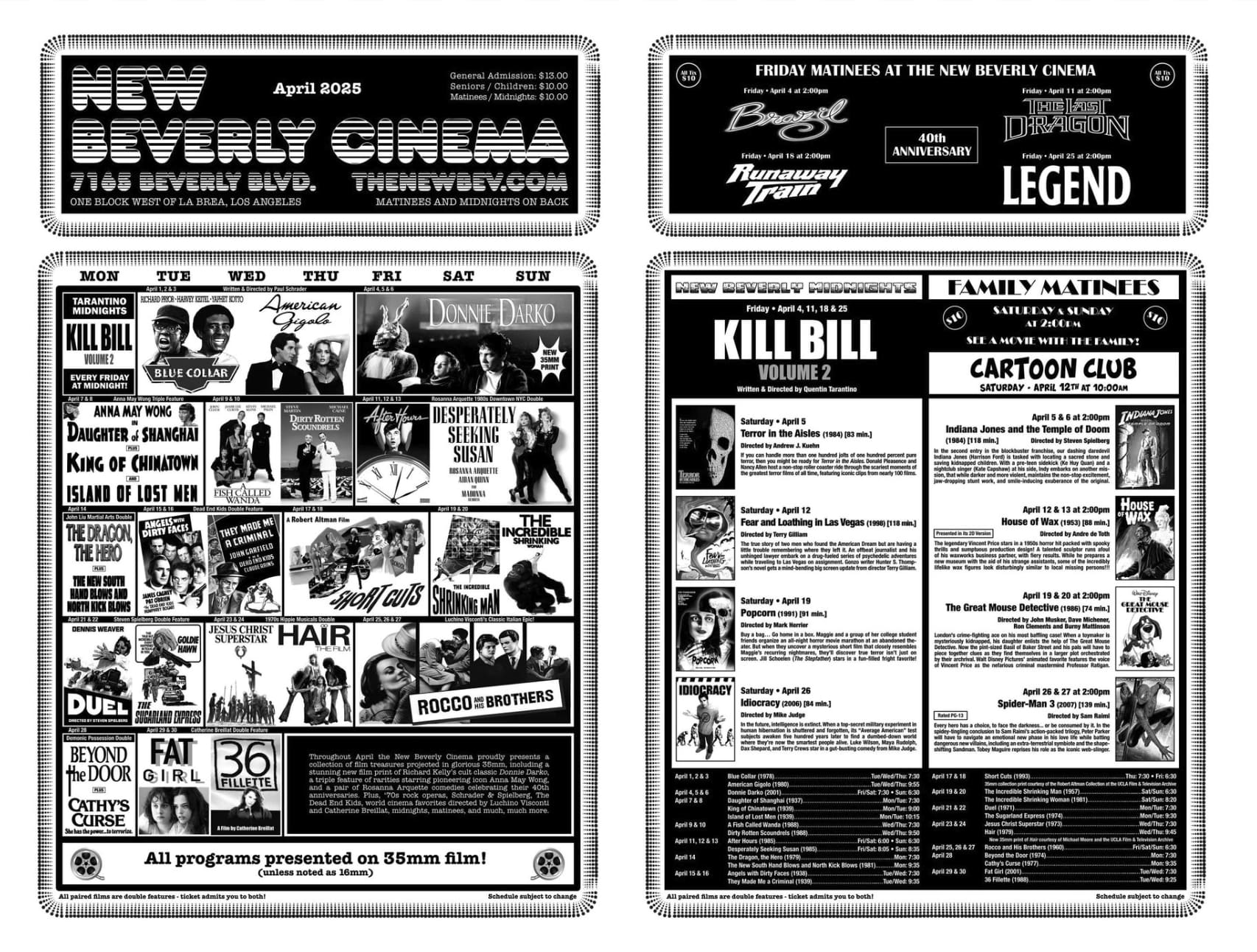

"I'd say a lot of people are in their late teens, early twenties," explained Sean Tayler, the 24-year-old programmer for Brisbane's New Farm Cinema in Mullins' piece. "It does skew young." It is a sentiment that echoes across many territories with cinema operators that you speak to lately. While Hollywood tentpoles are still struggling to find their audiences post-pandemic and post-strikes, young audiences are opting for old films.

A Counterintuitive Revival

For years, the prevailing narrative has been one of cinema's gradual demise. First came VHS, then DVD, then streaming platforms offering endless content at the touch of a button on any device. The COVID-19 pandemic seemed poised to deliver the final blow, forcing cinemas worldwide to shutter their doors. Yet something unexpected emerged in the aftermath.

According to Michael Phillips of the Chicago Tribune, writing in February 2025 ("You know who's suddenly flocking to old movies in Chicago? Young audiences"), the demographic shift has been remarkable. Phillips quoted Mimi Plauché, Chicago International Film Festival artistic director, who noted: "Our largest demographic group is now the 25- to 35-year-olds. Over half the festival audience is now under 45. That's a huge change from when I first started—back when it was lopsided toward people over 50."

Mark Anastasio, director of programming at the four-screen Coolidge Corner Theatre in Brookline, Massachusetts, confirmed this trend to IndieWire's Brian Welk ("How to Get Young Audiences in Theaters? Show Old Movies") in April 202 4. "The increase in interest in repertory has been huge," Anastasio said. "We've responded by screening more than ever." From 2019 to 2023, repertory programming jumped from 10 to 30 percent of the theater's total revenue.

Even Fathom Events, which organises limited-run screenings in mainstream multiplex chains, has witnessed this surge. According to company data shared with IndieWire, its top seven Studio Ghibli films earned 142 percent more at the box office in 2023 than in 2022. It's not just arthouse theaters seeing the benefit—the repertory renaissance is reaching suburban multiplexes, too. In the UK, Park Circus, which handles library titles for large and small cinema circuits is reporting similar surges in interest and bookings.

Digital Platforms Fuelling Physical Experiences

Counterintuitively, many industry experts believe digital platforms, particularly Letterboxd, have been instrumental in this revival. Launched in 2011, Letterboxd has grown from 1.8 million users in March 2020 to 12 million by February 2024, as reported by Tom Shone in The Guardian's December 2024 article "Covid was supposed to kill cinema – but did lockdown and gen Z save cinephilia?"

Gemma Gracewood, Letterboxd's editor-in-chief, told The Guardian: "Covid lockdowns were when we started to see a significant growth in our membership. People were using Letterboxd to explore filmographies and go deeper into film histories than they had done before." Letterboxd has become both a film school and a forum for collective curation.

This online exploration has directly translated to offline attendance. In Mullins' piece, Mark Cosgrove of Bristol's Watershed recalled programming Edward Yang's 2000 film "Yi Yi" in a small auditorium, expecting perhaps 40 attendees. "We ended up moving it into a bigger screen and we got an audience of 170. A large percentage of that audience was young people," he noted. The film's popularity wasn't random—it sits at number 11 on Letterboxd's Top 250 narrative features.

Jon Dieringer, founder of the arthouse and repertory resource Screen Slate, suggested to The Guardian that this online-to-offline pipeline represents a form of cultural discovery: "There's definitely places in the US like the Metrograph that trends on Letterboxd and can influence getting a restoration. That's how you get something like a restoration of 'Millennium Mambo' or 'Possession.'"

Beyond Digital Fatigue

While digital platforms might be the roadmap guiding young viewers to these films, the experience they seek is distinctly analogue. As Abe Beame wrote in The Ringer's March 2024 feature "The Future of Film May Just Be Old Movies," the appeal extends beyond mere content consumption.

"What I realized is that repertory cinema is a type of church and its adherents are ridiculous, unreasonable zealots dedicated to its allegedly antiquated faith," Beame wrote after visiting Quentin Tarantino's New Beverly Cinema in Los Angeles for a screening of "Bullitt." The cinema specialises in only screening repertory films in 35mm.

Ingrid Diekmann, programmer for Sydney's Golden Age Cinema, offered a more pragmatic explanation to Mullins: "We were all forced to consume so much 'content'. I wouldn't even call it media. It's moving wallpaper essentially and I think we all consumed about as much of that as we could stand."

This sentiment was echoed by Kristian Connelly, programmer for Melbourne's Cinema Nova, who told Mullins: "Streaming kind of gives the illusion of having this huge amount of choice. But in fact, there isn't a lot there. And a lot of it is crap." Anyone who has spent ten to twenty minutes fruitlessly scrolling through their personalised Netflix menu would be tempted to agree with her.

For twenty-something film students Parker Constantine and Flynn Boffo, who organise repertory screenings at the Australian Film Television and Radio School, the appeal lies in the physicality of the experience—the scratches on the screen, the dust marks, and splices. As Flynn explained to Mullins: "It's a new thing to us. We're somewhat mystified by it."

The physical aspects of film-watching—from the fragility of celluloid to the communal aspect of sitting in a darkened room with strangers—provides what Melbourne's Astor Theatre programmer Zak Hepburn described as an "experiential" quality. He compared cinema-going to concert attendance, emphasising the shared cultural moment that can't be replicated at home.

Commercial Implications

The industry has taken notice. Sony recently purchased the Alamo Drafthouse chain, a move that coincided with the 2022 sunsetting of the Paramount Decrees—the 1948 Supreme Court decision that had prevented studios from owning cinema chains. Netflix has acquired landmark theaters including Los Angeles's Egyptian Theatre and New York's Paris Theatre, both known for showing repertory and/or arthouse films.

These strategic moves suggest that studios see theatrical exhibition, even repertory screenings, as valuable components of the movie-watching ecosystem. As Steven O'Dell, Sony's president of international theatrical distribution, told IndieWire: "If anybody wants to doubt that we believe in our future, to invest in cinema is the biggest statement we could make. And we don't do it to make a statement, we do it to make money, so we're doing it because we believe in the industry."

Lisa Bunnell, Focus Features' distribution president, explained to IndieWire the importance of repertory programming for building brand loyalty: "It's about getting people to understand not only your current films but your past films," she said. "We make sure that we spotlight not only who we are now but what we were in the past."

Beyond Nostalgia

While repertory screenings have always attracted certain audiences, what makes the current trend remarkable is both its scale and its demographics. Previous waves of repertory enthusiasm typically centred on nostalgia—baby boomers revisiting the films of their youth. Today's young audiences, however, are discovering films that predate their birth by decades.

In some ways, this represents a cultural correction. As Bloomberg entertainment reporter Lucas Shaw told The Ringer, studios had been pushing for shorter theatrical windows even before the pandemic, responding to perceived changes in viewing habits. What they perhaps underestimated was the human desire for communal experiences and cultural discovery that can't be replicated through algorithms.

For Micah Gottlieb, founder of the Los Angeles-based nomadic film series Mezzanine, this resurgence recalls cinema's golden age. As he told The Ringer: "The 1960s was the peak of international world cinema. You had regular people getting into Antonioni, Bergman, Godard... Whenever they released a movie, it was national news, and cinema was really vital. And I guess what I wonder is, why can't we have a version of this again?" It seems like that is what is now happening.

A Cultural Counterbalance

The revival of repertory cinema also appears to be a Darwinian response to the current film landscape. As The Ringer noted, nearly every decision the studios have made since the turn of the century has inadvertently strengthened repertory cinema as a counterbalance in the industry.

With major studios focusing increasingly on franchise films and intellectual property, independent cinemas have been forced to seek alternatives. Adam Roberts, owner of Kansas City's Screenland Armour, told IndieWire that his theater has even opted to screen repertory Disney titles rather than their first-run offerings due to the studio's restrictive policies. No doubt the rental split on those film are also more in favour of the cinema.

This evolution may also reflect changing cultural tastes. According to the Chicago Tribune's Phillips, what worked at repertory houses in 2023 would have been unimaginable even a few years earlier: sold-out screenings of Béla Tarr's 24-year-old "Werckmeister Harmonies" and retrospectives of Mike Leigh and Edward Yang. Béla Tarr was also an unlikely marquee draw recently in Bristol (as we will explore in a future post).

Community in an Algorithmic Age

Perhaps most significantly, this repertory renaissance speaks to a desire for authentic cultural experiences in an age of algorithmic curation. Young film students Parker Constantine and Flynn Boffo emphasised to Mullins the power of personal connection in their screenings.

"There's such a nice feeling of someone picking out a film and being like, this is my favourite, you're gonna sit down, we're gonna watch it, and we're gonna go to the pub and talk about it afterwards," Constantine said.

This hunger for connection was touchingly illustrated by Boffo recounting their screening of Peter Greenaway's controversial "The Cook, The Thief, His Wife and Her Lover": "Someone said 'I don't know if this was my kind of film, but I definitely enjoyed watching it with everyone.' And I think that's the biggest thing for us is, you're not always going to like the film, but you're going to like the experience."

In a digital world that has atomised cultural consumption into individually tailored feeds and personalised recommendations, the deliberate act of engaging with art communally represents a conscious step away from algorithmic isolation. These young cinephiles are not rejecting digital modernity wholesale—indeed, many discovered these films through digital platforms—but rather seeking to complement it with experiences that algorithms cannot replicate.

The growing appetite for repertory cinema among young audiences suggests that, far from killing theatrical exhibition, the digital era may have simply redefined its purpose. No longer the primary delivery mechanism for new releases, the cinema is increasingly valued as a site of cultural pilgrimage—a place where cinematic history is not just preserved but actively experienced by new generations of devoted pilgrims.

As Mullins concluded in his essay, reflecting on his young friend Noah's enraptured response to "The Holy Mountain": "He's been up one of cinema's holy mountains and nothing will be the same again." Hollywood, take note.

The New Wave: How Generation Z Fell in Love with Cinema's Classics